The Almost On-Demand Economy

Or… why you should stop trying to copy Uber and come up with a model that makes sense.

Obviously there are a ton of Uber for X startups out there. It’s become fashionable to call everything part of the on-demand economy.

While the on-demand economy feels like all sunshine and roses for consumers, there lurks a danger of unsustainability in on-demand startups. If we want some of these wonderful VC-funded miracles to last in our lives, we need to change the demands a bit as consumers. And “on-demand” startups need to wise up and provide “almost on-demand” solutions that meet the needs of the consumer while enabling a profitable business model.

The joke around San Francisco nowadays is that there is a transfer of wealth going on from VCs to consumers because VCs are funding these negative gross margin businesses like free food, delivery, parking, rides, etc.

One of the reasons these businesses have negative gross margins is because the startup goes to great lengths to provide on-demand services. On-demand food delivery, or parking, or laundry cleaning, or massages, or whatever – is very expensive and operationally complex to deliver. Without massive scale, startups need to come up with alternate and often, expensive solutions to deliver on-demand. The great instigator in all of this, Uber, paid drivers full time in the early days to just drive and be available in case someone hailed a ride.

It’s my belief that several of the on-demand startups that are heralded today as innovators (I’m not naming names – if you know me well, you know which ones I’m bearish on) will be joining Homejoy sometime in 2016. I think they are operating at negative margins and can only survive if a) they have consistent access to capital, b) they increase price, c) drastically reduce COGS, or d) change their business model.

Regarding access to capital – the late stage private markets are already very fearful about the perceived high valuations and have scaled back investment activity in recent months. Re: increasing price, if some of these companies start raising the price, I believe that churn will skyrocket and the CAC:LTV ratio simply will not hold. This leaves the companies with the option of drastically reducing COGS, which is possible but very hard and requires lots of time and iteration. Operational improvements tend to come in small increments, 10% here, 10% there. Over time, those 10% improvements compound to an incredibly efficient operation, but it’s unclear whether or not companies will have enough time to make these improvements before running out of cash. Then, lastly, there is an option to change the business model.

Several companies will have to change their business model to survive. Options could include charging subscription fees (the gym membership model) or adapting to an almost on-demand model.

Let’s look at a few alternatives that are doing things in smart and sustainable ways that I consider “almost on-demand:”

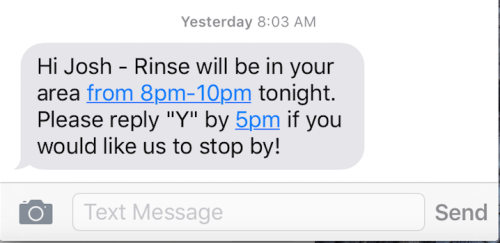

1) Rinse – Rinse is an “almost on-demand” dry-cleaning and laundry service. The founders of the company have experience as operators in this industry and rather than just copying Uber, they thought carefully about what really made sense for this vertical. Rather than pushing a button and requesting an order, they have planned routes a couple times per week. This fits perfectly with my own usage patterns of doing dry cleaning once in a while. I hardly ever need rush or 24 hour service. This route planning allows Rinse to get much higher route density than an on-demand model and therefore keep COGS relatively low.

2) Hux – Hux is an almost on-demand housecleaning startup based in Atlanta. They have employed a different model than a Handy or Homejoy. In addition to booking available slots, they empower individual house-cleaners to promote themselves and employ a “single-commit buyer-picks” marketplace. Handy and Homejoy employ a supplier-picks marketplace where the buyer just picks a time slot and then it’s first come first served for whoever wants to claim the job. This can work to fill the demand, but it does not allow for buyers and suppliers to build a long term relationship. This type of an approach is very good for marketplaces where the buyers prefer specific providers (non-commodity or high trust element) and are not typically in a rush situation (scheduling a couple days away is just fine).

3) Munchery – Food delivery startups are promising faster and faster delivery times. The drivers cart tons of food around in their car and the company tries to plan accordingly based on forecasted demand in a particular area. This is great for the consumer, but means that the food delivery startup has to over-staff certain areas and typically has quite a bit of food waste. In addition, it can lead to a negative consumer experience if items sell out unexpectedly. It’s a very tricky balancing act for the company. In contrast, see how Munchery handles things below with pre-orders and selected delivery time windows. Admittedly, it’s a bummer to have to plan ahead as a consumer, but is it really that hard to decide earlier in the day if you’re going to be home for dinner? I’m sure this pre-order system makes Munchery’s operations much easier, more efficient for route planning, and less wasteful of excess food.

Kudos to the companies out there that are focused on building long-term sustainable businesses and aren’t caught up in chasing the hype around Uber and on-demand.

Forge your own path forward.

jonathanchizick liked this

wadevaughn liked this

jbreinlinger posted this

jbreinlinger posted this