Reflections Prompted By A Conversation Between a16z Crypto Leader Chris Dixon & The Verge’s Nilay Patel

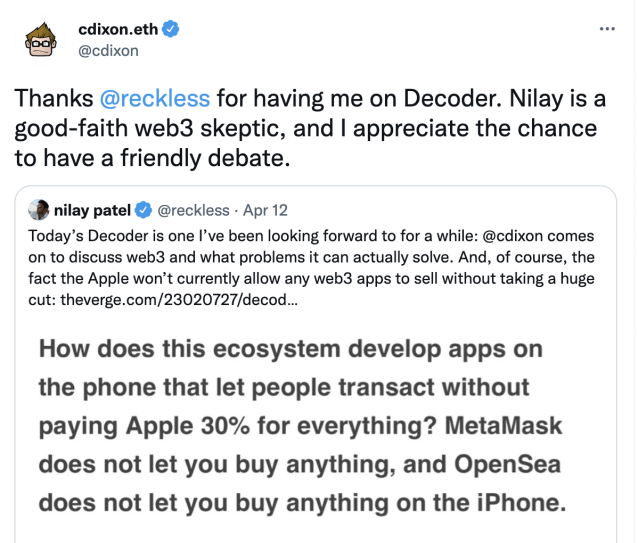

“Good-Faith Skeptic.” It’s a characterization that has been tossing around in my head since reading Chris Dixon’s tweet about his interview with the Verge’s Nilay Patel. It was crypto true believer in a conversation with a crypto skeptic, but containing a foundation of mutual respect, curiosity and, I think, a fundamental love of technology. Here’s a transcript of the podcast if you want to click over to the source material.

For purposes of crypto, consider me an optimistic skeptic? Maybe one with less tolerance (and more judgment) of what I consider to be actors in the ecosystem who are greedy, exploitive, or selfish, but also certainly not willing to write off the entirety of what we’re seeing. My most personal interest is in the collective ownership aspects, having long believed that the only structure which can beat the network effects of entrenched marketplaces are cooperatives, where the participants ARE the platform.

But I should also be transparent with you. Nothing else in this post is going to take a ‘side’ with regards to cartoon apes, decentralized token protocols, or stablecoin pegs. Instead this is going to be about skepticism and what gets deemed good-faith or not.

Here are the primary characteristics, for me in this moment, of what it means to be a “good-faith” skeptic:

- Enters the discussion without desire to win but instead to understand and be understood.

- Believes accomplishing the above will ‘grow the pie’ of understanding for general benefit, rather than carving up a fixed pie.

- Can be hard on the problem without being hard on the person.

- Accepts that they may be incorrect, have had a different experience than others, evolve their own beliefs. And gives the other person the same courtesy.

- Within the confines of the discussion space itself, if it’s shared, protects the other person from abuse and actively discourages ‘their team’ from doing so.

There’s no way this is an exhaustive list but it’s what comes to mind for me.

I don’t think good-faith has to ignore questions of what incentives an individual holds which might cause them to believe a certain idea or act a certain way.

I don’t think good-faith has to be ‘polite,’ in a manner which suggests detachment from realities which could be causing real people real harm.

I don’t think good-faith should include apologies for being in disagreement. You can feel upset or sympathetic for conflict caused by disagreement without being sorry for the disagreement itself.

I hope to be a good-faith skeptic in many cases where I disagree with a group’s beliefs or the current narrative. But this also doesn’t mean that every person or every concept deserves evergreen good-faith. As the saying goes, the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house, and I can see some people suggesting that “good-faith” skepticism is disagreement theater, where you have different POVs but still all go to country club for dinner after the discussion.

We live in cyclone of bad-faith accusations but also the world is a place where different people are disproportionately impacted by the current state of the world. I personally would find it challenging to have good-faith conversations with individuals who hold extreme perspectives on limiting human rights.

You tell me, what have you experienced as good-faith skepticism vs bad-faith? Are there other characteristics you look for, or methods for deciding when a person/perspective is worthy of good-faith attention instead of ignoring them?